CRE Finance World Summer 2015

40

s students continue to arrive on college campuses across

the country every fall, developers have continued building

apartment complexes to keep up with demand for student

housing, resulting in a large spike in off-campus construction

in the last several years. According to a March 2015 article

in the National Real Estate Investor, developers added approximately

60,000 and 63,000 beds to the student housing inventory in 2013

and 2014, respectively. While construction ahead of the 2015-2016

school year is expected to be lower at just 48,000, this still exceeds

inventory growth for this property type at the peak of the market in

2008. The CMBS industry has also seen an uptick in the number

of student housing properties being securitized in transactions.

Based on a study of loan data conducted by DBRS, the increase

of these securitizations seems to mimic the frequency of watchlist,

delinquency and special servicing events associated with student

housing properties across CMBS transactions issued in 2010 and

later. This would lead one to believe that loans secured by student

housing properties are more prone to default than those secured

by traditional multifamily properties.

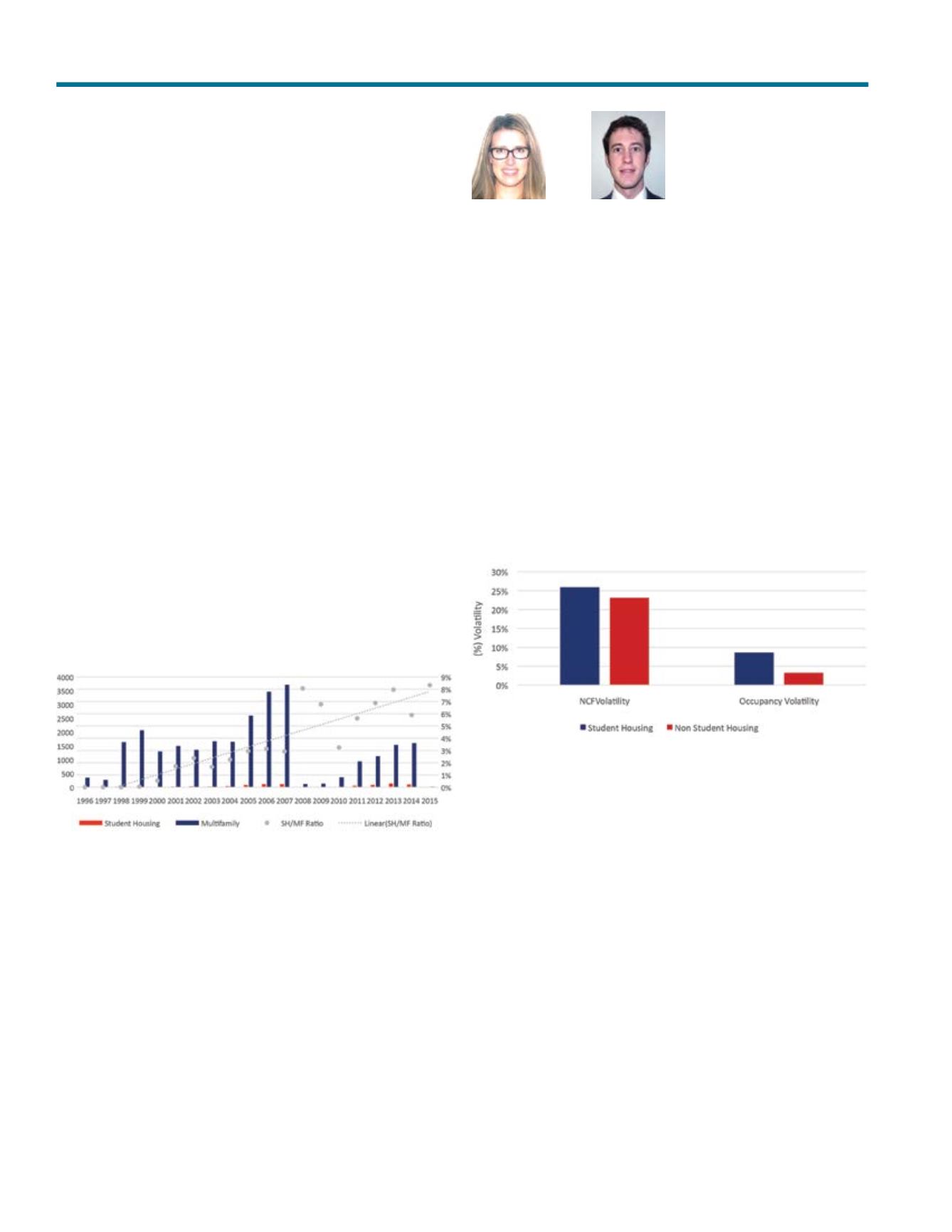

Exhibit 1

US CMBS: Student Housing (% of total Multifamily Issuance)

As a sub-category of multifamily properties, student housing assets

have been deemed by DBRS to carry a greater probability of default

given their vulnerability to shifts in occupancy and cash flow. All

leases generally start and expire in the same month, depending

on whether nine-month or 12- month leases are required. If an

operator misses during the critical, concentrated leasing period

for college students who need to secure housing ahead of the fall

semester, it becomes challenging to make up the lost ground during

the school year and maintain market rental rates. In comparison,

traditional multifamily properties benefit from a more diverse tenant

profile with lease expiration dates that are spread more evenly

throughout the year. The result is two-fold: greater occupancy

volatility and greater cash flow volatility for student housing

properties compared to non-student housing properties.

The graph below compares the volatility

1

of occupancy and net

cash flow between student housing and non-student housing

properties securitized in CMBS transactions since 2010. The year-

over-year occupancy and net cash flow changes were calculated

using the FYE financials as reported in the investor reporting

package (IRP) for each financial year reported.

Exhibit 2

US CMBS: NCF & Occupancy Volatilities for SH/NonSH

Perhaps the most significant performance factor for any student

housing venture is its proximity to a college campus. This geographic

limitation means that developers have had to find other ways to

market a property’s appeal. Many in the industry have commented

on the growing list of demands student tenants bring to the table.

These include tenant lounges, resort-style pools, game rooms,

fitness centers, tanning beds, campus shuttles and high end finishes

such as granite counter tops, stainless steel appliances and upgraded

flooring. It is not uncommon for property managers to offer leasing

incentives such as gift cards or flat-screen televisions, and many,

if not all, of these amenities are deemed necessary to remain

competitive as new student housing properties are added to the

market. It would follow, then, that replacement costs and operating

expenditures for these properties are higher than those that do not

cater to students.

A

Student Housing Performance in CMBSJorge Lopez

Financial Analyst,

Global CMBS,

Global Structured Finance

DBRS

Roxanna Tangen

Assistant Vice President,

Global CMBS,

Global Structured Finance

DBRS